There’s no denying that art is powerful. Art can help empower local communities and play an important role in their development. In the most straightforward manner, artists can choose to highlight informality in different ways, by directly depicting the plight of residents in exhibitions, for example; be it in the context of a specific settlement, country, or even a disaster. Another option is a more nuanced and research-based approach, such as “Egyptian Urban Action”—the multimedia exhibition organised by architect, urban planner and researcher Omnia Khalil; that used documentary, maps and other media to address the lack of planning of Egyptian informal settlements, and to advocate for a participatory approach.

In Nang Lerng, in the old town of Bangkok, the local community has been using art to strengthen community ties, and to serve as a platform for their negotiations with the Crown Property Bureau (CPB), the government organisation that owns the land they are living on. The E-Lerng artist collective in Nang Lerng, led by community leader P’Dang and her daughter Nammon, has been exploring new ways of highlighting the value of this community and the benefit of them staying on the lands they have occupied for generations. E-Lerng has also organised a series of events to draw attention to some of the underlying issues they are facing: from the proliferation of lice amongst children due to cramped living conditions, to the failure of traditional negotiations.

Events with the participation of external parties—as well as international collaborations—are very constructive for the community in Nang Lerng. As P’Dang explained, such events shed a positive light on the community vis-à-vis government institutions. It also offers a ground for collaboration and sharing that is non-political—unlike social issues, or even architecture since the tenure of the community is contentious.

In light of the existing interest for art among the residents of Nang Lerng, in late 2017 we built on our existing relation with the E-Lerng artist collective through a series of movement workshops and dance performances.

Organising the workshops and performances

The initial idea for this event was born through an informal discussion between P’Dang and Nammon, Ploy Yamtree from Openspace, and Mike Hornblow an artist from New Zealand. We tried to match their personal and social development interests, thinking that this event could be a feasibility study, inviting close collaborators to help make it happen. On the funding issue, we agreed that we would cover all costs ourselves—the artists cover their own airfares, the organisers provide accommodation, light and sound systems, and the Openspace team serves as the main coordinator for this event.

In November 2017, we were joined by five artists from Asia and Australasia for a series of workshops and performances: Tony Yap (Australia/Malaysia), Agung Gunawan (Indonesia), Takashi Takiguchi (Japan), Benjamin Allen (Australia), and Mike Hornblow (Australia/New Zealand).

Tony Yap

Agung Gunawan

Takashi Takiguchi

Mike Hornblow

Benjamin Allen

These artists have been interacting with local communities in different settings over many years. Tony is the Creative Director of Melaka Art and Performance Festival (MAPFest), a site-specific festival in Malaysia, now in its tenth year. Agung has been involved with organising festivals in Java, Indonesia, and has been instrumental in reviving Bantengan bull spirit practices in Batu, which is deeply anchored in the beliefs of the local community. Takashi started his career as a social worker and has been very interested in community issues. Benjamin has a background in Parkour, which is anchored in an awareness of one’s surroundings. Mike has been working closely with Tony, Agung, Takeshi, and Benjamin for many years as an artist, organiser, and academic.

Embodied Movement

The artists chose embodied movement as a theme, as they considered it a good fit for this community. First and foremost, embodied movement does not require any previous dance experience or any kind of aptitude; that means that it is open to all, irrespective of age, body type and athletic ability. The second element is that it is extremely place-specific: the performances use and depend upon the environment and are therefore respectful of both the physical place and the people who inhabit it.

Embodied movement workshop run by Mike Honblow

Embodied movement ties experience with the built environment and the natural world, a concept that connects well with people in South East Asia, who already have a strong belief in the spirit of a place: a recognition that a given site has its own consciousness that emerges from the different elements in place, but also the spirits that embody each thing. Embodied movement augments the potential for a sense of place, by recognising that we are sharing the space with things that are not human.

Aside from site specificity, psychophysical performance practice is crucial in understanding embodied movement: it is the idea that the body is more than the physical, more than the movement of limbs in specific positions at a given speed. It acknowledges the emotional aspect of the body, and this in turn is what connects with audiences. “The notion of embodiment can be seen as an awareness of your body and its capacity: how it moves in the world, how it connects; how it feels inside, how you connect with other people, and the space around you. It’s not just the movement of limbs but also includes sounds, smells, and other sensory experiences. Embodiment brings an awareness of your interaction with other people, and the sense of a place”, explains Mike.

Embodied movement workshop run by Tony Yap

The space between the physical and the emotional, that in-between area, is harder to quantify but it is where you can truly connect with the spirit of the place. “Atmosphere is probably the most tangible concept for the spirit of place: each place has a smell, sounds, is moulded by history, touched by the people who are there. It’s the transformative element that is most interesting in a performance, but it is also something that anyone can become aware of through embodied movement”, says Mike.

Embodied movement: workshops and performances in Nang Lerng

Nang Lerng is an interesting stage for embodied movement, as it offers a beautiful built environment and strong relations with the community and its leaders, as well as an existing art tradition. The E-Lerng collective practices, performs and teaches the traditional Thai Chatri dance and play, continuously promoting their local culture. The collaboration with these five artists is interesting in the sense that it is introducing some new art forms to the community, giving them a new canvas to experiment with.

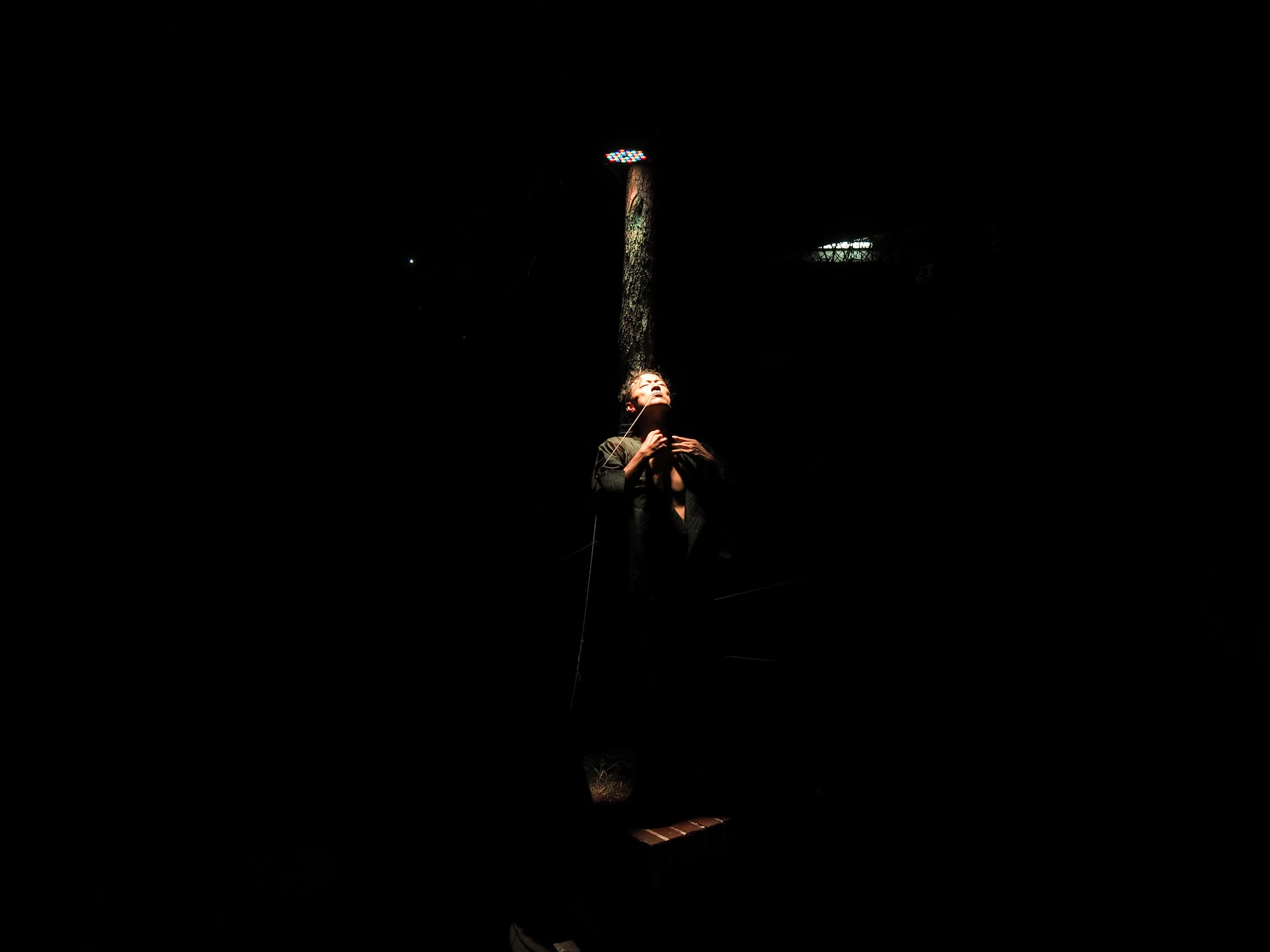

Embodied movement performance by Takashi Takigushi

The project comprised two distinct parts: a performance by four of the artists, and two workshops—one run by Mike and Benjamin, and one run by Tony. 15 to 20 people participated in each workshop, some of whom were community members, while the performances drew a big crowd from within the community, as well as a few visitors. The performances took place at the Wat Care Nang Lerng temple, both because of its spacious grounds and central location, and for its significance for the local people.

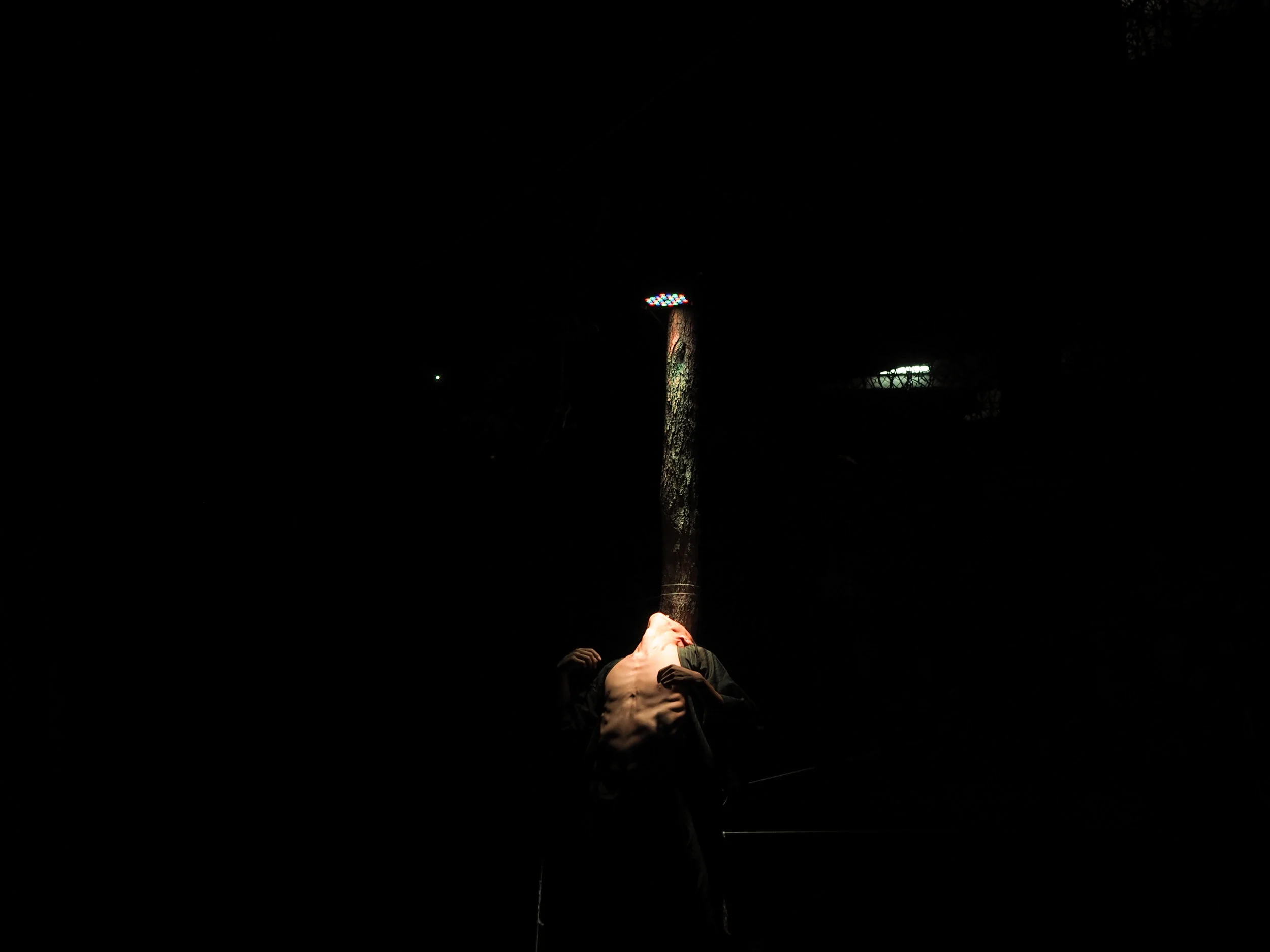

Embodied movement performance by Agung Gunawan

Each performer chose a spot around the temple that resonated with him the most. Takashi and Tony chose to work with the columbarium wall, a wall storing the cinerary urns, while Agung chose the space between the columbarium and the main temple. The location of the performances impressed the community, as it indicated that the dancers were not afraid of ghosts. Takashi, in particular, chose a narrow space near the columbarium that ends in a dark corner, from where he emerged pulled on a cart by Benjamin. This was a great opportunity to transform the perception of the space, from something to be feared into something to be enjoyed.“This is one of the levels on which they connected with the performance, as it was accessing their beliefs about that area, and inviting them to live this space in a new way”, explains Ploy.

Embodied movement performance by Tony Yap

Looking to the future

The workshops and performances served as an introduction to a new form of dance for the people of Nang Lerng, as well as a new opportunity to collaborate with artists outside the community. Workshops may now be organised on a yearly basis, and may even be combined with the community festival in Nang Lerng. Working within the boundaries of the Nang Lerng festival is exciting as it would allow the artists to marry new forms of dance with the traditional Chatri dance. Having an international presence in the Nang Lerng festival would also promote the development of the community, garnering attention within Bangkok. This first project is a feasibility study to tease out the possibilities for a long-term relation between the artists, Openspace and the community.

“I am very inspired by the old cinema and the market in Nang Lerng. I have done a lot of work with food and performance already, and it’s interesting as food is a leveller for people: we all need it and all process it in the same way, while the hospitality aspect allows for conviviality amongst people. Working around the market could be an interesting possibility in the future”, explains Mike.

Plans for a follow-up event in 2018 will seek to extend the 2017 pilot study, with more artists, workshops and performances. The pilot format allows for experimentation, while ensuring that the community is still interested in furthering this relationship, and for responding to changing conditions or opportunities in the future. “We could also experiment with other media, with the background of the cinema, or work with architecture students on something related to mapping”, says Mike.

P’Dang has also expressed an interest in allowing other communities to participate in the festival, or inviting people from other communities to come to Nang Lerng, thus opening up the community and creating new links. The festivals that have taken place in Nang Lerng so far have targeted underprivileged youths and children—for example, those who do not attend school or those involved in gangs—to empower them. What they have observed is that being involved and being knowledgeable about their community has increased their pride, well-being, and sense of place within the community.

The takeaway from such experiences is clear: an event or collaboration does not have to be overtly political to be impactful, and empowering for the communities involved. Showing the value of areas that are too often disregarded, especially in light of the mounting evictions of Bangkok slum areas and the uncertainty the residents live in, has an intrinsic value in itself. It can change perceptions. And perceptions matter.